Evolutionary Algorithms for CSS - FoundersHack24 writeup

Introduction

A couple of weeks ago, some friends and I did a weekend hackathon and built a web app that lets you add a line of code to your frontend and watch your website evolve in real-time.

The idea was that we could use some kind of customer engagement metric from your site (clicks, checkouts, etc) to guide an evolutionary algorithm which mutates your css in order to improve said metric. In this post, I benchmark our v1 algorithm and then make it better.

The version that we built over the weekend uses a simple binary tournament algorithm and generates ‘offspring’ - winning css classes - using gpt-4. I was inspired by the paper Evolution through Large Models' by Joel Lehman et al., where LLM's were shown to be good at acting as mutator functions; an intelligent heuristic for the random search that is evolution.

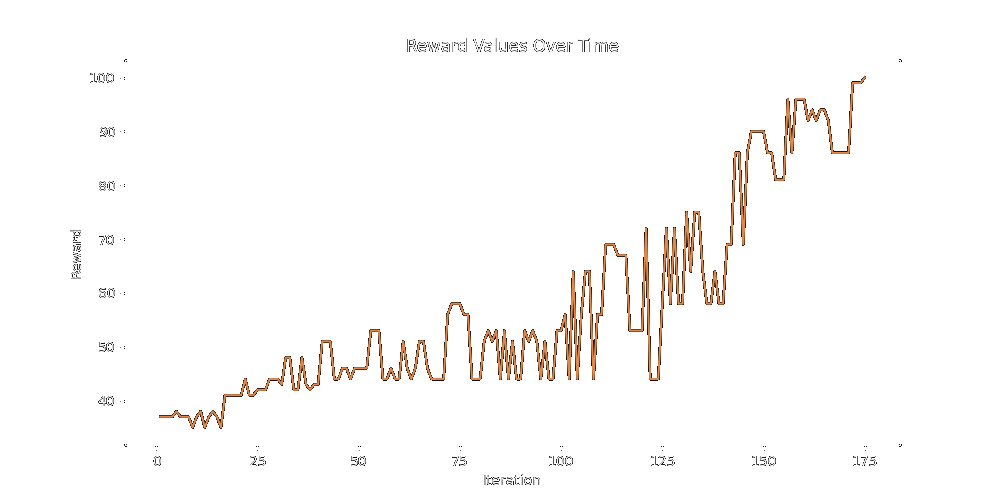

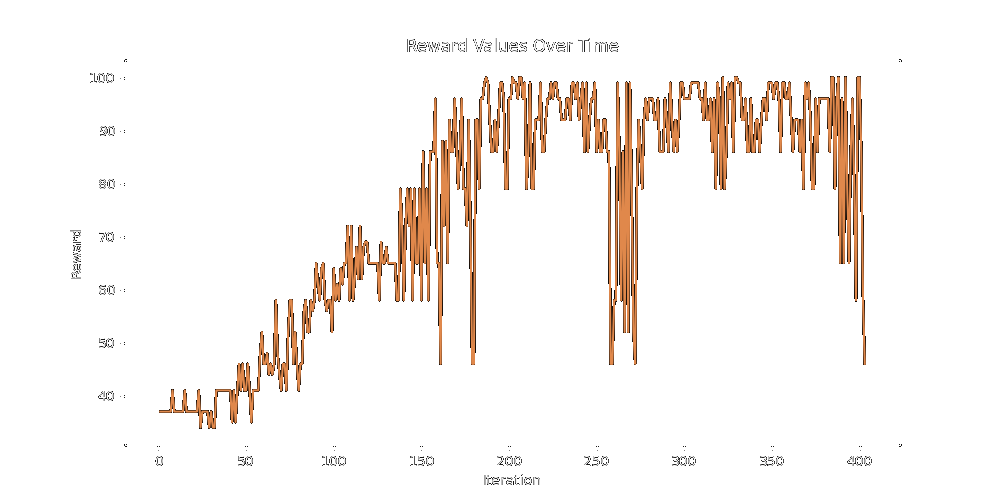

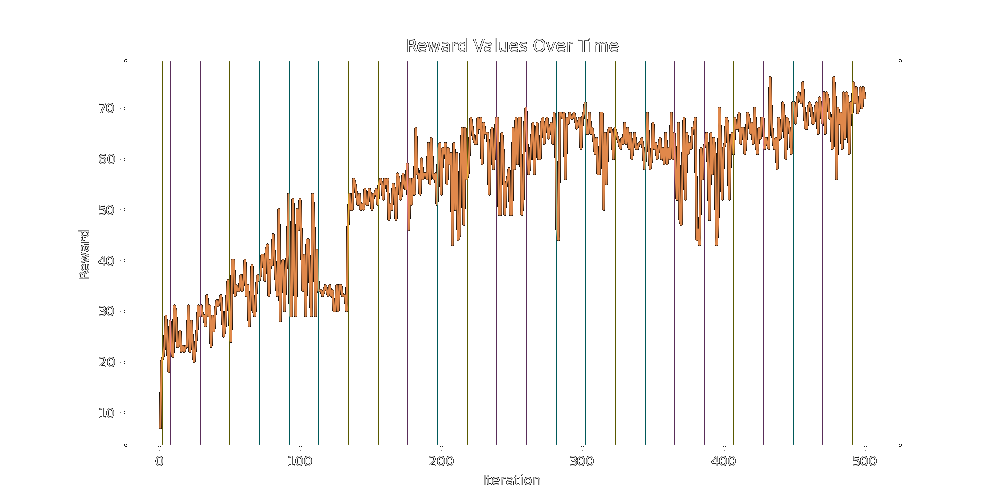

The algorithm written during the hackathon showed promising results; it learned well when tested on a mock reward function that calculated error over the css class's padding but did poorly over more complicated reward functions involving several variables. Here's a graph from the hackathon that shows the algorithm puffing along in simulation with a hand-written reward function that says Big Button Good (Reward increases the closer the css class is to padding-x-100):

This blog post details experiments with 4 different types of generator functions:

- Vector momentum Based generation

- Lineage based generation

- Mutation-description based generation

- Mixture of generation functions

Just to preface, I am not a scientist, this is not a paper, and I don't have unlimited OpenAI credits. So, even though basically every 'test' I've run needs to be run at least 10 times and results need to be averaged, I will not be running anything more than once or twice. This is both because there are so many obvious improvements needing to be made that I feel safe assuming current results are not enormously important

Algorithm Overview

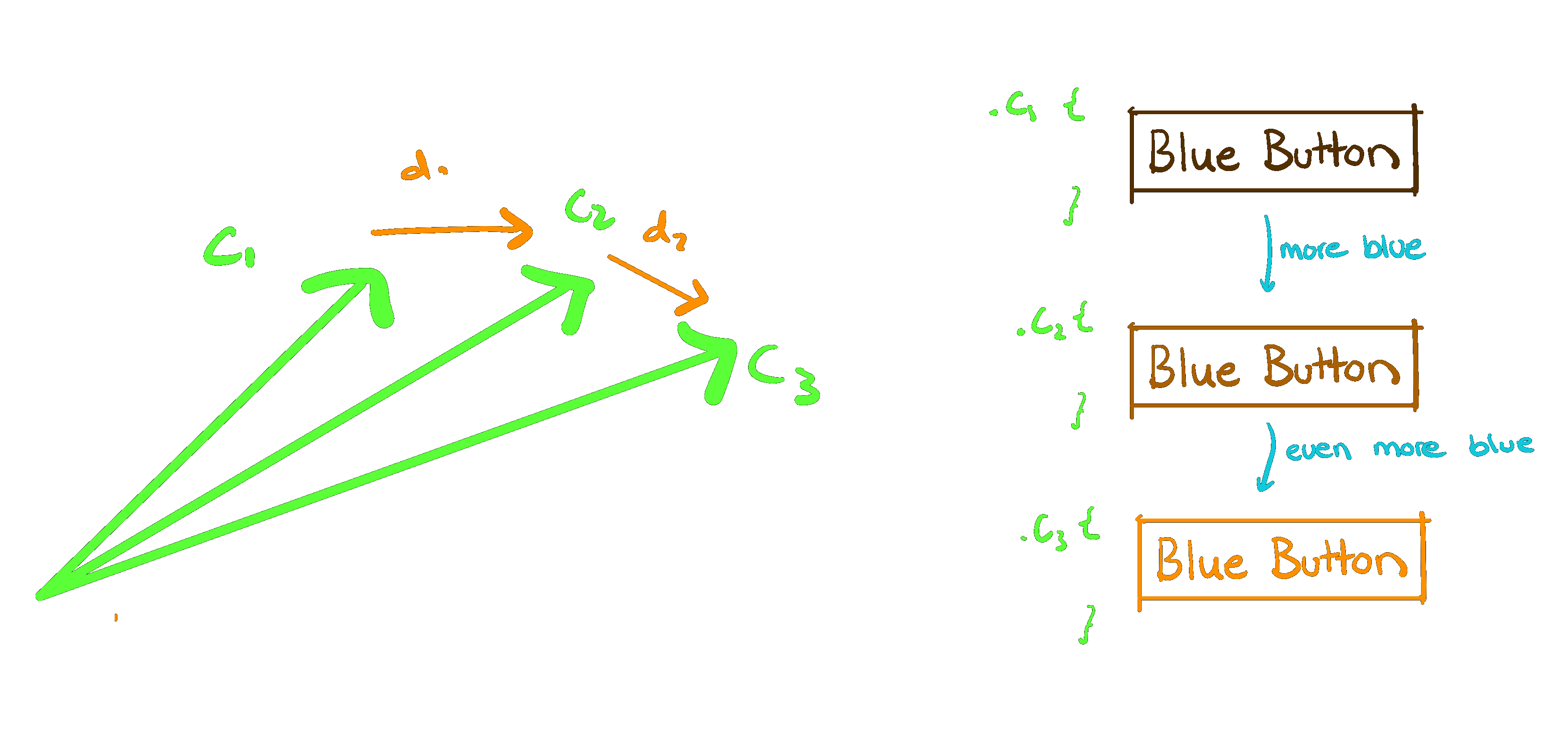

To talk about how it works, instead of saying 'css-class' I'm going to say 'node'. This is because our 'css-classes' have been all shoved into 'nodes' that belong to a 'tree'. The nodes all get a score based on the engagement metrics we pull from your site (for now just number of clicks). Once each node has collected a significant enough data sample, 'children' nodes are generated from the nodes with the best engagement.

.png)

The child generating function is the most important part of the algorithm. Just naively prompting GPT to give you a gaggle of possible children that are in the vicinity of the parent's css instinctively seems pretty inefficient (but actually works well).

Vector Momentum Based Generation

This heuristic was dreamt up at 3 or 4 in the morning during the hackathon. Essentially, we calculate what we think the next best css class is going to be using vector embeddings, and then filter down the possible children based on their difference from the predicted vector.

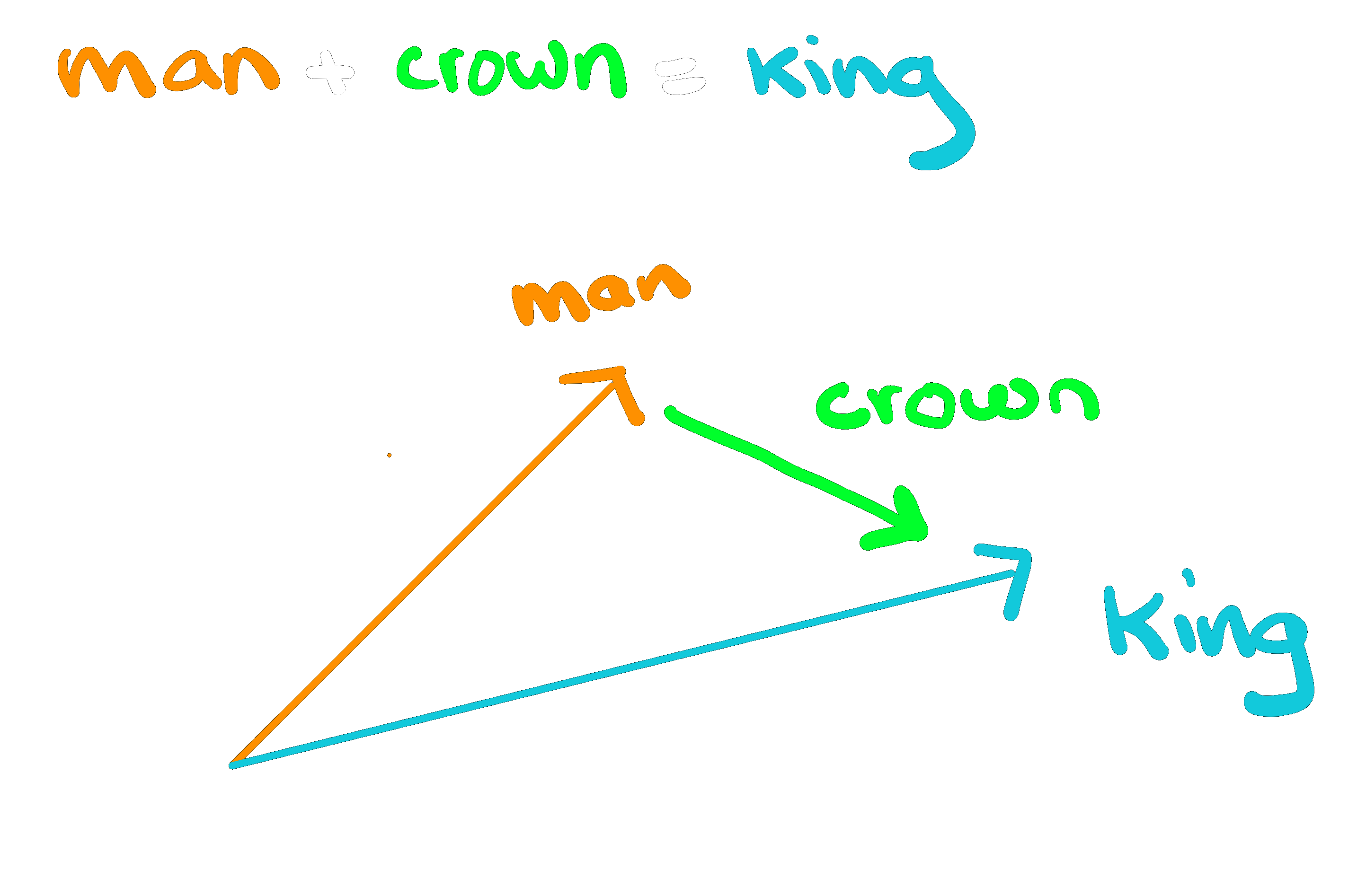

Firstly, the css of each node gets vectorized using OpenAI's text embedding api. Vector embeddings are useful because they allow us to capture the semantics of a piece of text and stuff it inside a long number.

For example, if you take and add together the vectors for the words 'man' and 'crown' you'll end up with the vector of 'king'. Similarly, King - Man + Woman ≈ Queen. You can check out the original word2vec repo from Google here.

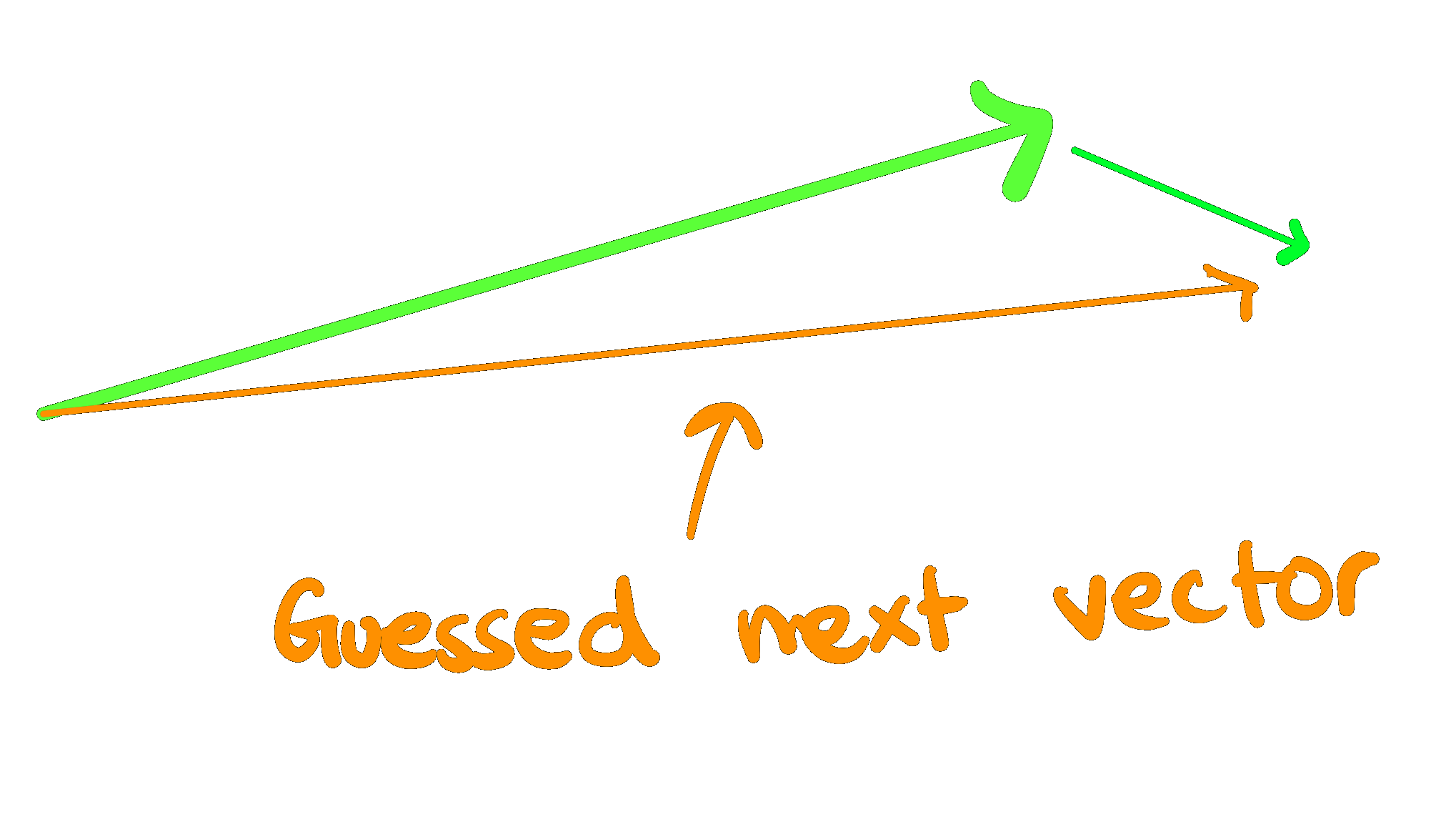

The algorithm written during the hackathon used a 'momentum' vector, or the average direction of change along a node's direct ancestors (each node in the walk between the root node and child node in question), to predict which potential offspring of a node were most likely to succeed.

The calculated momentum vector from node to root is summed with the node's embedding to get a predicted vector embedding.

Then, using this predicted vector embedding, a batch of possible children is filtered down by taking the top-k similar children to the predicted vector.

The motivation here is that if you're a node that's getting to reproduce, you're the best of your batch, and all of your ancestors were the best of their batch. If there's some common 'direction' to all of the successful mutation in your lineage, it's likely that perhaps continuing to move in that direction might be a good idea. Filtering on the prediction vector should increase the odds that the change from parent to child is the type of change that has been working best so far, allowing the optimal component to be reached faster

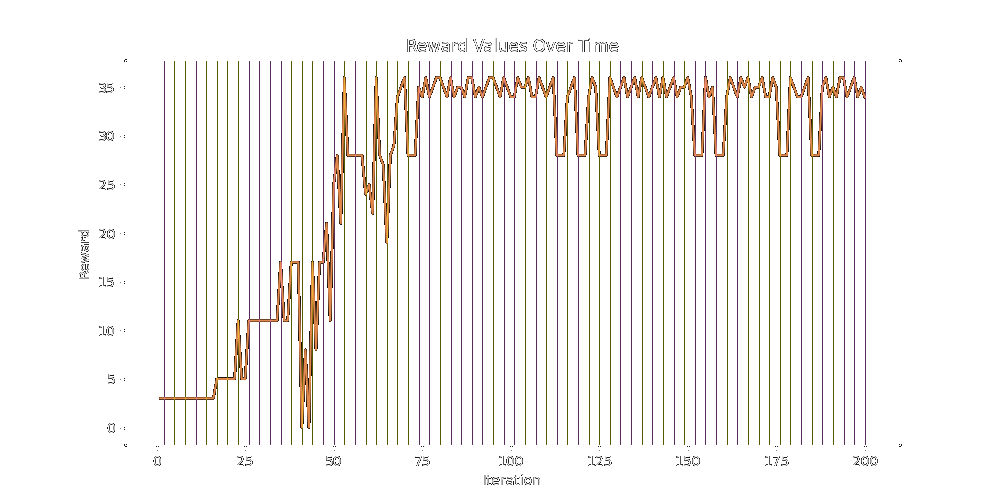

Now - does it work?? Here are the graphs for momentum vs no momentum, where the target css is

padding: 100px 76px;

background-color: #3418db;

border-radius: 15px;

font-size: 42px;

color: #3518df;Momentum Method:

Default Method:

Although not definitive, the momentum method seems to have a nonlinear climb at the start, whilst the default climbs very linearly. My guess for why the default method is so linear is that the LLM is always generating children roughly equally different from their parent at each step. Ignoring the differences in slope between the two, both graphs reassuringly reached max reward in a reasonable amount of time and then bounced around angrily unable to find any more reward.

My worries about the efficiency of the vector approach are as follows:

- The differences between two vectors representing slightly different css classes are almost arbitrary and small enough to be meaningless.

- Euclidean distance may not be the best way to compare these vectors given how similar they are. If I have more time in the future I might revisit the function with a cosine similarity or other distance function.

- By filtering on momentum other, possibly better, options may be lost.

- A well prompted GPT-4 can probably generate the next css component in a sequence better than even 1000 css classes filtered on a prediction vector. (This one may depend heavily on sequences of optimal changes found in the real world vs sequences where just a single parameter is getting changed)

- There might be some cooler way to generate a css class from an embedding, i.e run a model somehow combining the prompt with the vector. Unsure.

- Vector momentum is not making a huge difference implemented as is (but will still might be very useful in aligning components with your brand color palette, identity, etc)

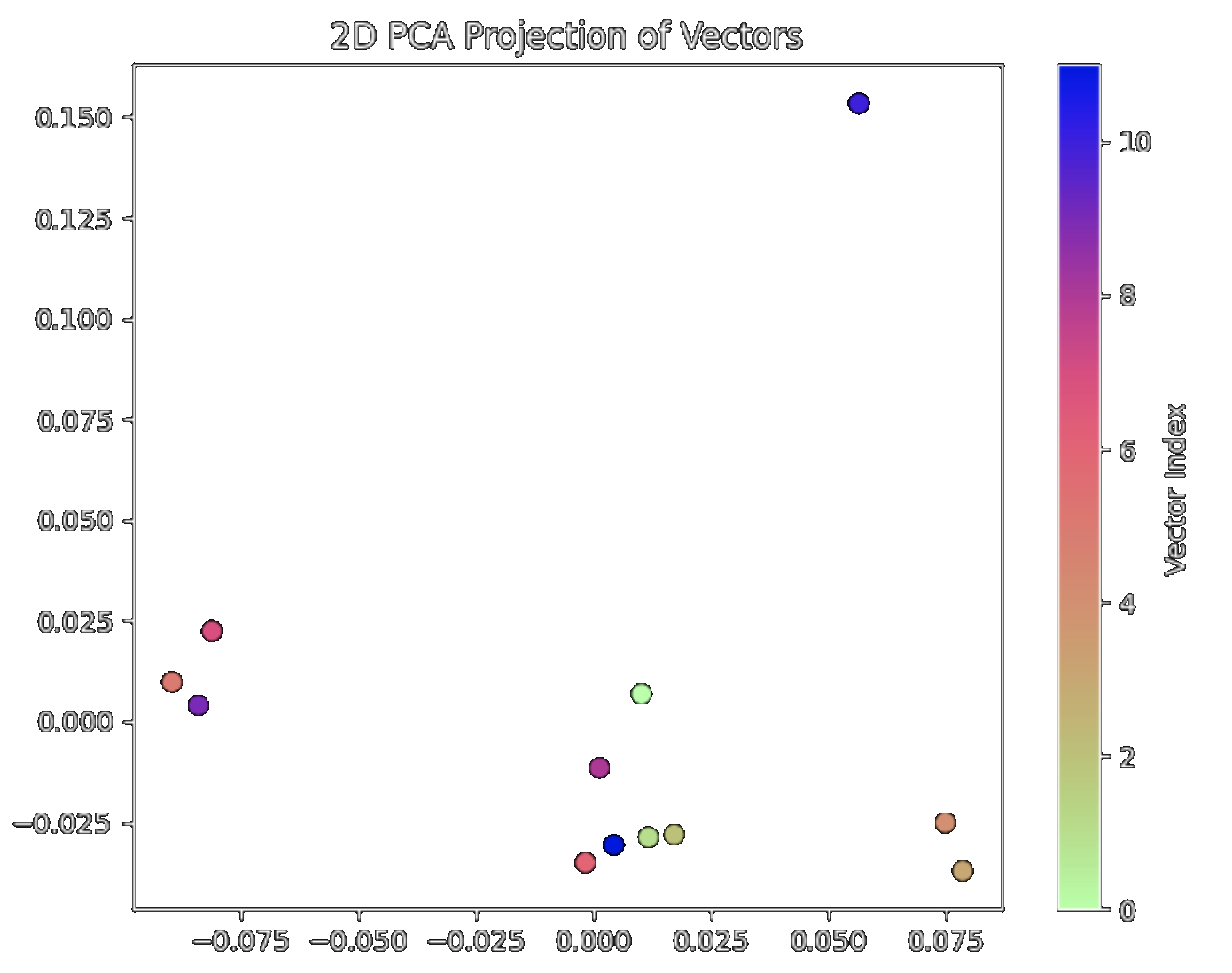

To quickly peek into my first worry, here's what the embeddings on the path for the reward graph shown above looks like:

This (along with visualizations of other trials) just looks like noise to me.

Multivariate Reward

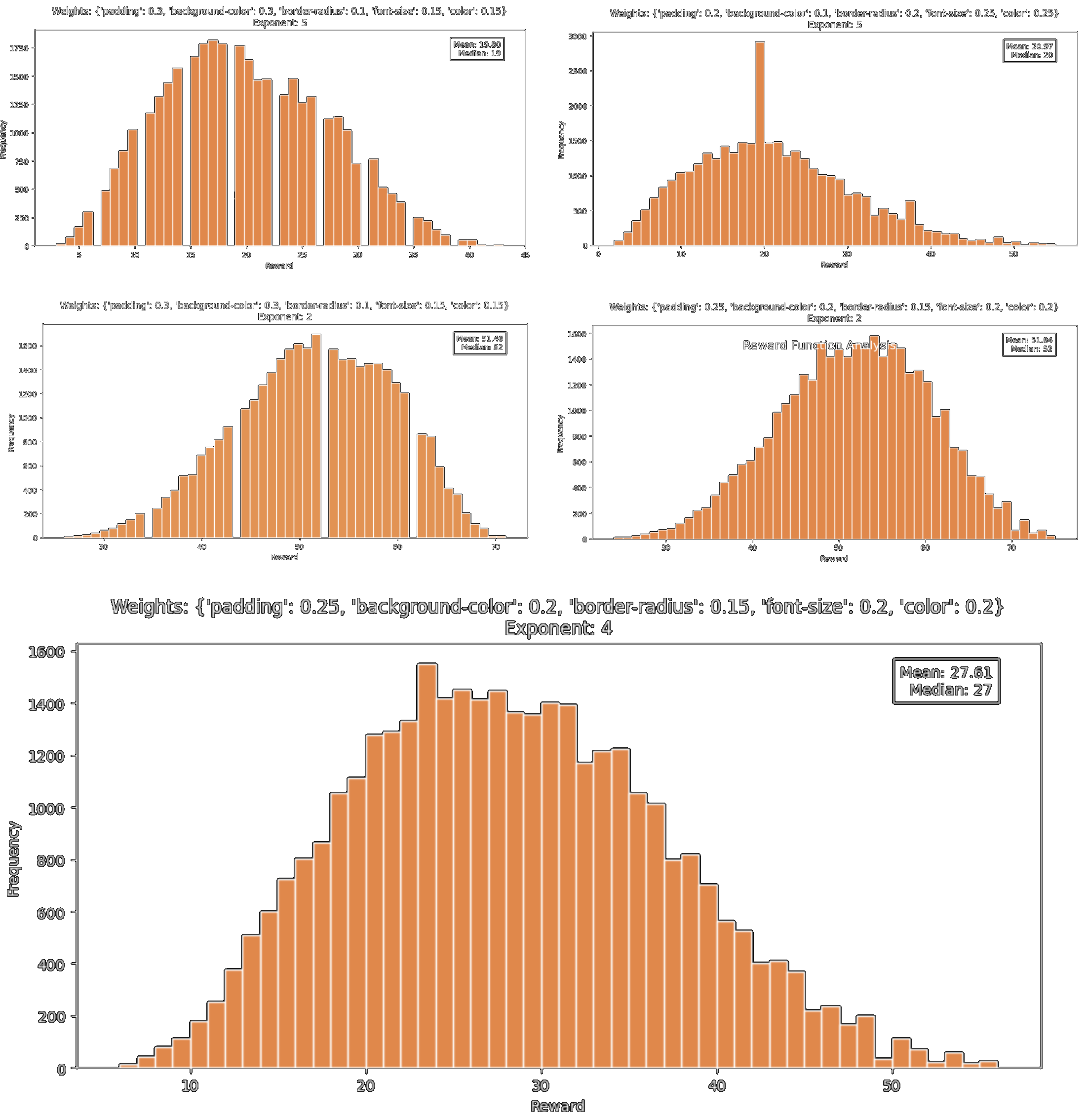

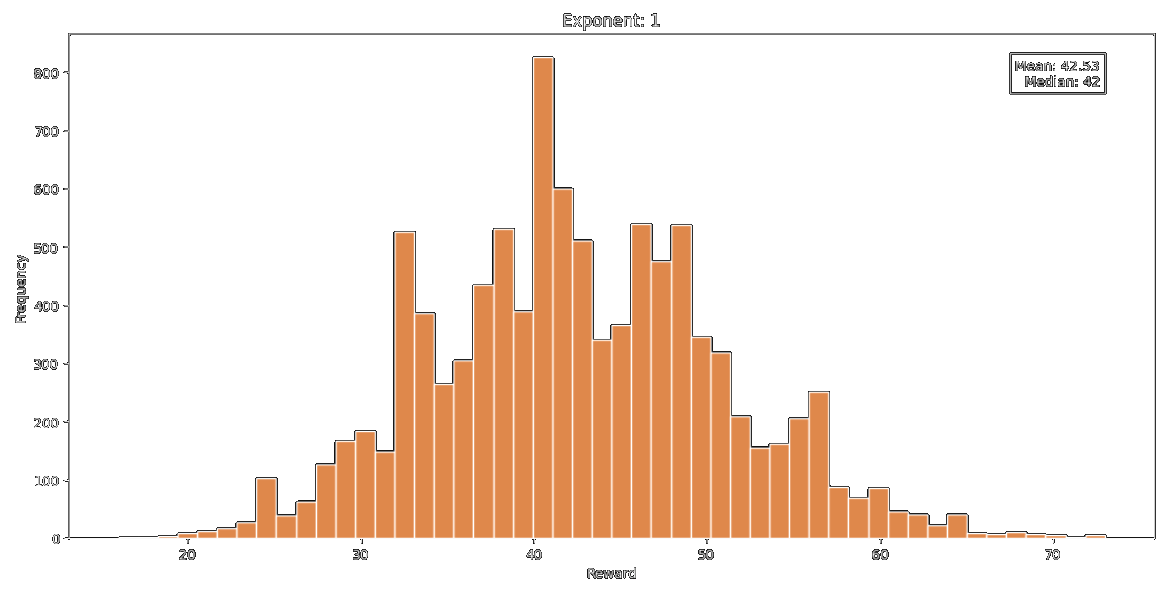

Testing on the single variable reward function like before isn't very enlightening. So, getting a little more serious, I wrote a multivariate reward function that calculates a loss over the padding, background-color, color, font-size, and border-radius fields individually and then weights and sums them up. To test the reward function, I ran a loop that would generate ~100,000 random css classes and record the reward. Below you can see the distributions of reward on the reward function parameterized by a couple of different sets of weights.

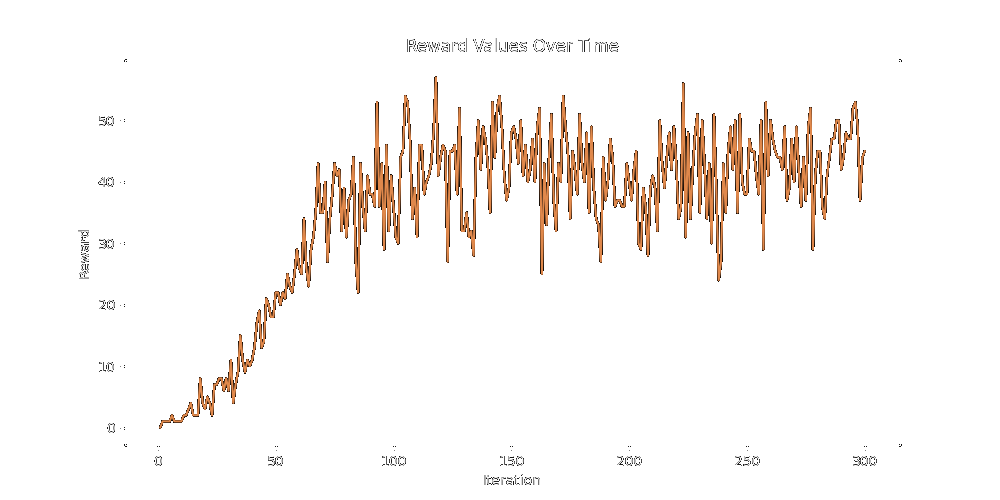

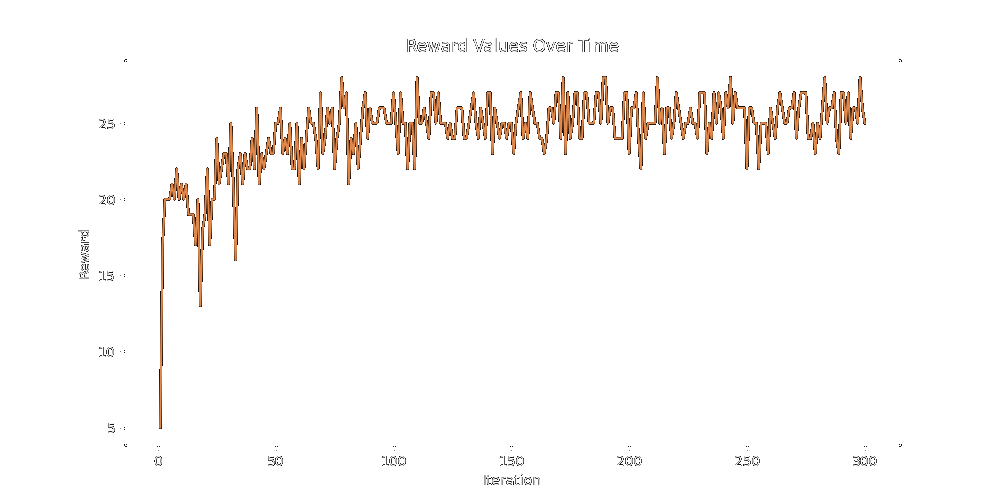

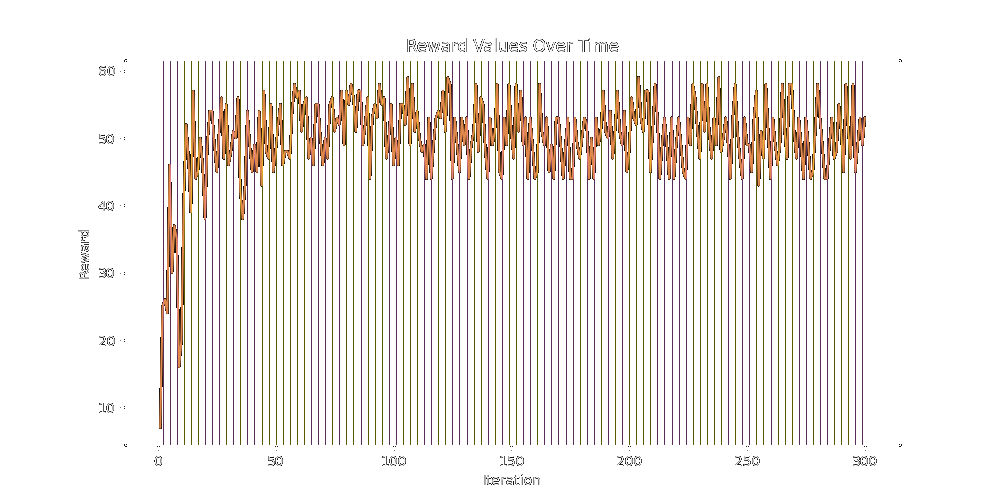

I put the graph on the bottom at the bottom because it's the one we're going to use to test the vector momentum method. It's the one we're going to use because it's the best looking and has a nice tail. Running our momentum method for 300 epochs (5 children per evolution) on the multivariate reward function above, we get this (nice) graph:

This is a good start! We get up to ~50 reward pretty quickly, which was on the very long tail end of our distribution. While the resulting css class isn't perfect (that would be a reward of 100), it's pretty close.

This is a good start! We get up to ~50 reward pretty quickly, which was on the very long tail end of our distribution. While the resulting css class isn't perfect (that would be a reward of 100), it's pretty close.

On the left is the button we gave the algorithm when we started our test, the middle is the output of running the algorithm on the start button, and the right is the target button.

Lineage Based Generation

Now, instead of vector momentum, I tried giving the child generator prompt an ordered list of the parent prompts (the winners) and asked for them to extrapolate to the next children.

Here's the prompt:

prompt = f''' This is a test. Take a look at these CSS classes and try and figure out the trend.

Please generate {num_to_gen} components you believe could be the next class in the sequence.

Ensure all the fields the parent classes use are present in your answers. Return the css in a JSON object in the format: {json_structure}

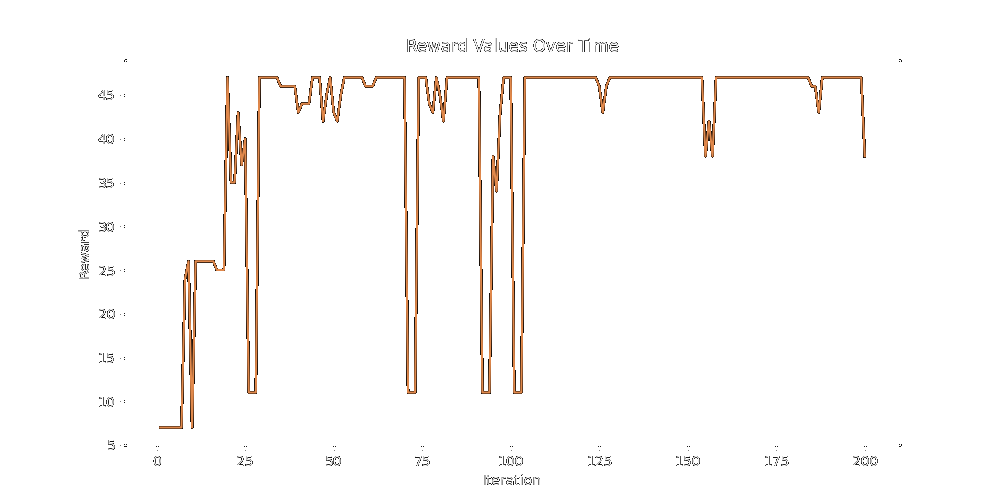

Keep the classname exactly the same as the original. Here is your sequence: { " ".join(f"{i}: {p}\n" for i, p in enumerate(parents)) } '''When run with this as the only child generating function, the LLM extrapolates too quickly. If it first (correctly) generates a button with 12 padding, then 45, then 105, it will never figure out that the optimal padding is 80 because it will keep predicting paddings that are larger than its ancestors. You'd get stuck with the best node being from your 3rd round of evolution. This was not terribly effective:

To combat this, a mix of the original generator function and the lineage generator function is used. This adds back noise to the children, and will break the spell of changes that trend only in one direction. Also, instead of looking at the entire lineage, the lineage generator function will only use the last 3 ancestors.

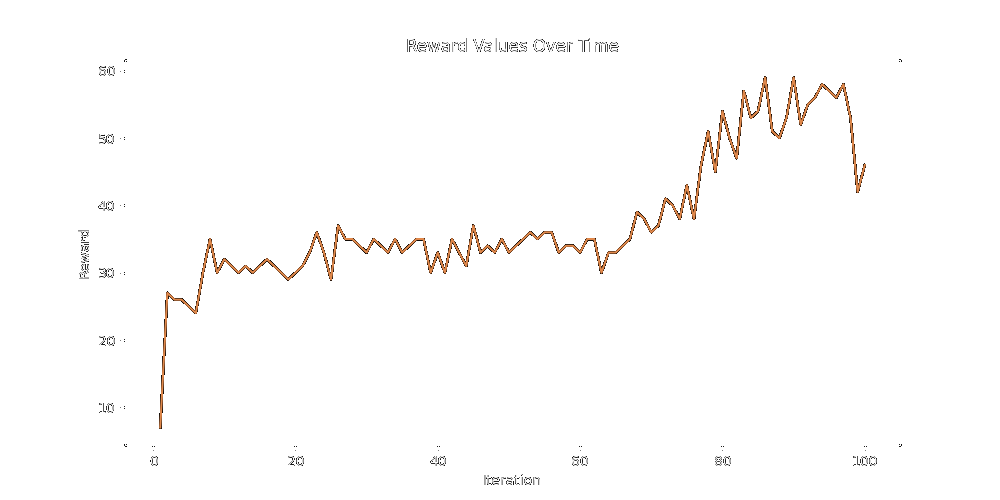

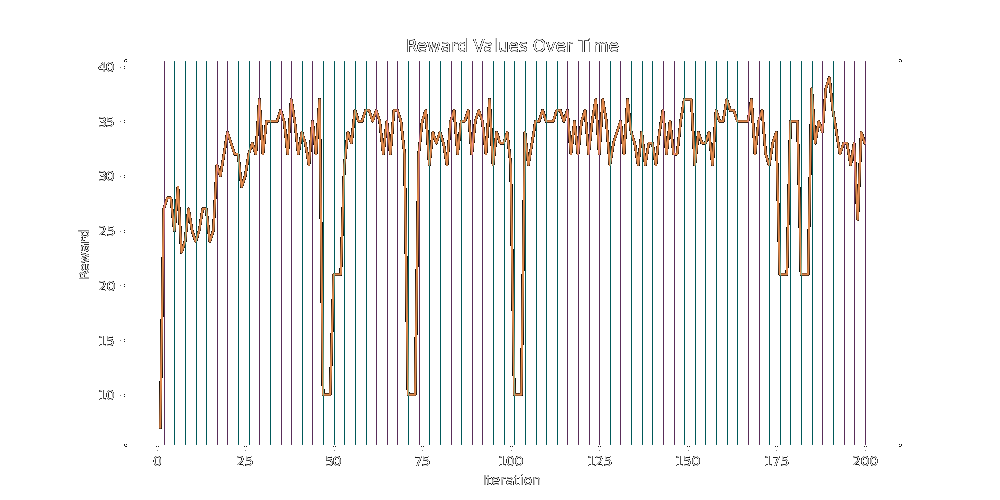

Here's a preliminary test of a 70% Default and 30% Lineage split for 100 iterations:

As you can see it mills around for a while until breaking out into good reward. My biggest worry about doing large scale generation work like this with LLMs is that the vast bulk of the LLM output space is not sufficiently covering the solution space, and if you don't inject enough 'creativity' into the LLM's search via an algorithm that forces it to move around in interesting ways you'll just end up mapping the output space of the LLM and won't find a good solution.

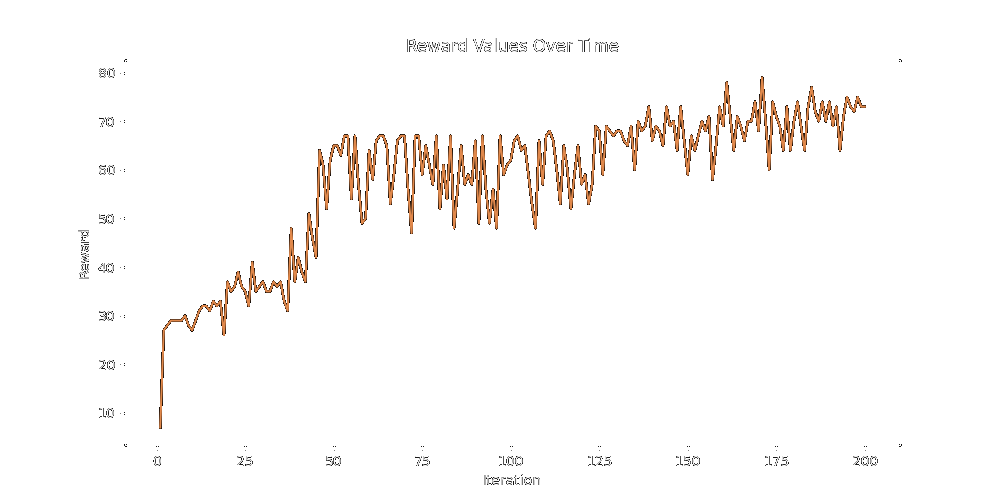

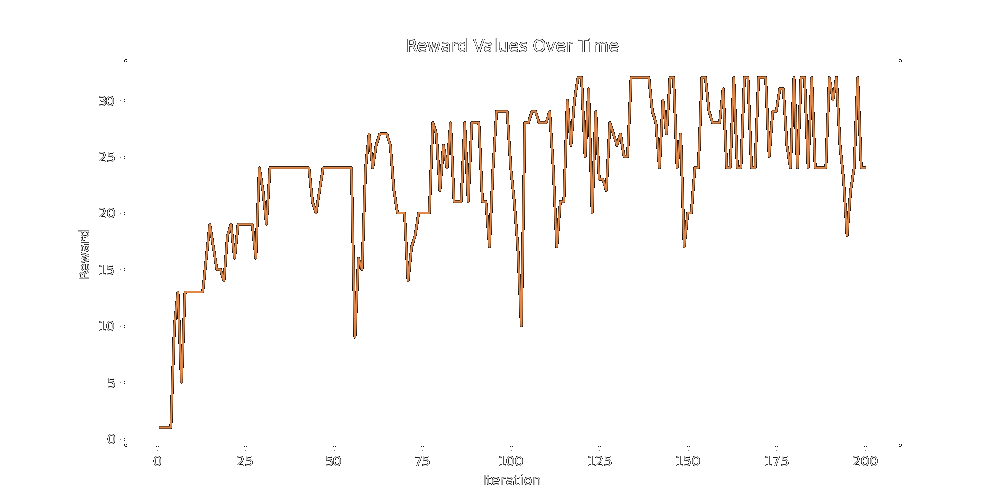

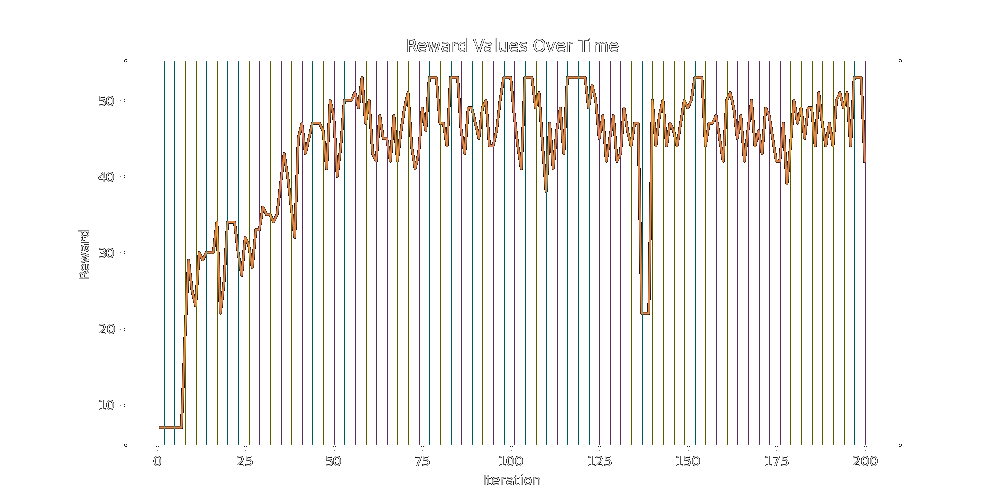

Here's a 60% Default 40% Lineage split run for 200 iterations:

Here's a final, longer run. As you can see, the reward peaks super fast, but plateaus out after that. Again, missing the margins on the reward but definitely getting the bulk of it. The lines are time-steps where offspring were evolved, green being a Default generation and blue being a Lineage Generation.

Again, absolutely gobbling up the bulk of the reward but never figuring out the finer details past that. For reference, here's the starting class, the target class, and the generated class.

.start {

padding: 0px 0px;

background-color: #ffffff;

border-radius: 0px;

font-size: 0px;

color: #ffffff;

}

.target {

padding: 200px 176px;

background-color: #3418db;

border-radius: 88px;

font-size: 12px;

color: #3518df;

}

.generated {

padding: 180px 170px;

background-color: #555555;

border-radius: 100px;

font-size: 12px;

color: #111111;

}

As you can see, aside from still not learning the blue at all (again), this isn't half bad.

Mutation Based Generation

Finally, inspired by the PromptBreeder paper from DeepMind, I implemented another alternative to the momentum function, in which a pool of 'mutation-descriptions' are used to direct the search.

This is done by generating possible 'mutation descriptions' with the prompt

f'''Given the following CSS and its performance metric:

CSS: {parent_css}

Performance Metric: {parent_performance}

Generate a concise mutation instruction that could potentially improve the CSS's performance.

The instruction should be actionable and focus on a single aspect of the CSS while not asking for a field to be explicitly set at a value. Limit your response to a single sentence of no more than 5 words.

Example outputs:

- "Increase padding"

- "Change background color to a warmer tone"

- "Reduce border-radius by half"

- ...

'''And then injecting our child-generating prompt with the mutation description as such:

f'''...Please generate {num_to_gen} components that are variations of {parent_node_css},

following this mutation instruction: "{mutation_description}"...'''Each mutation description has a fitness score which is updated based on the performance of the children it helps generate.

A pool of mutation descriptions is kept, and every 10 or 20 iterations the pool is culled, with the bottom 60% being replaced by variants of the surviving members of the pool. PromptBreeder found that First order hyper-mutation worked best, where you have an LLM generate a new mutation from a current mutation and then apply this new mutation to a task-prompt.

The core idea here is the same as the vector momentum and lineage-generation methods; We want to cultivate information on which improvements work and give that back to our child-rearing function.

However - prompt mutation alone isn't enough to crack the egg.

In fact it actually does pretty poorly, getting very much stuck at around 45 reward on the same simple multivariate reward function as the previous tests.

In hope that the meta-prompt would not pigeonhole when presented with a more challenging problem, I tested the mutation method over a reward function with 24 parameters instead of the 5 parameter function we've been using so far.

align-items: / 0.621125589650138 /

background-clip: / 1.8252509337491687 /

background-color: / 1.6482848792251787 /

border: / 1.5288701836976046 /

border-radius: / 0.5210176483709332 /

box-shadow: / 1.9239703248683404 /

box-sizing: / 1.7749016829736144 /

color: / 0.7975467967218579 /

cursor: / 1.870275016436737 /

display: / 0.9822250632948639 /

font-family: / 1.3746111768693745 /

font-size: / 1.746882083324551 /

font-weight: / 1.8948477490783098 /

justify-content: / 1.009001145196173 /

line-height: / 1.1422749890569817 /

margin: / 1.6049692785481726 /

min-height: / 1.2484012871457506 /

padding: / 0.6742505800171446 /

position: / 1.2342917940293587 /

text-decoration: / 1.0449603977198751 /

transition: / 1.1678218251236352 /

user-select: / 1.3563946984161854 /

While the graph is much more sane here, the mutation method can't break past 1/3 of the total reward on this either.

A 50% Default method (blue), 50% Lineage method (green) split doesn't do too much better on the 24 parameter reward function either, capping around 35 reward.

50% Lineage (green) 50% Mutation (red) does roughly the same:

A full 60-20-20 split of default-lineage-mutation (b-g-r) caps a little bit higher at 51:

HOWEVER, if we switch from the simple binary race to a wider search in which multiple candidate nodes are reproducing at once, we see a much steeper climb in reward over a much smaller number of generation events. I hadn't done this already because openai bill ($). In the following tests, children are generated from 4 different winners at each evolution step.

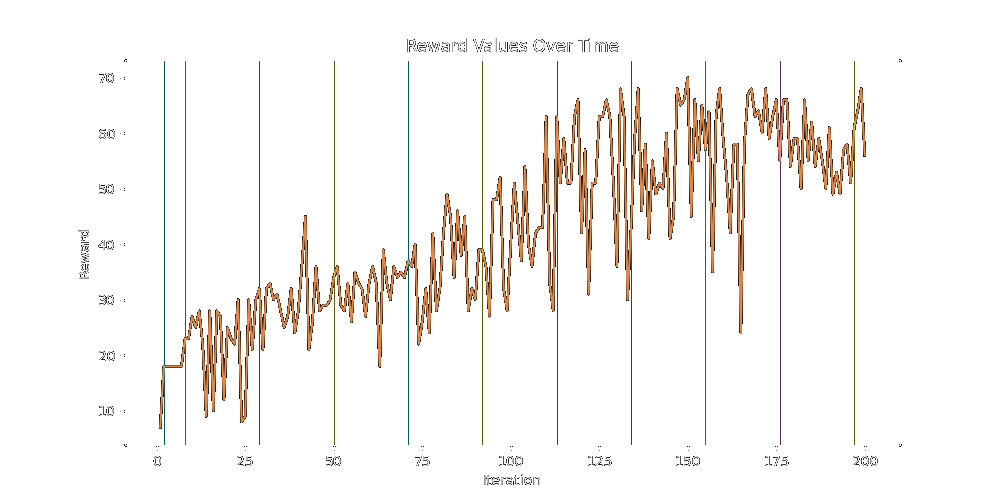

As a preliminary test of the 60-20-20 split, generating, we see the reward steadily climbing to 68 total reward.

Finally, attempting the wider search over twice as many iterations, we slowly break past the high 60's and into the mid 70s.

None of these algorithms seem great at finding reward on the margins, they do a good job finding the bulk of it.

While there is clearly lots more work to be done if anyone out there happens to want definitive answers (what even are those?), I am getting a little stir crazy applying these algorithms to 'Cascading Style Sheets'. So I going to leave it up to the reader as an exercise.

I will hopefully find time to do a more general and thorough dive into the vector momentum idea, as it might just show promise for many types of prediction problems.

Thanks for reading!