Issues with TMS' Fractional Dimensionality

Toy Models Of Superposition

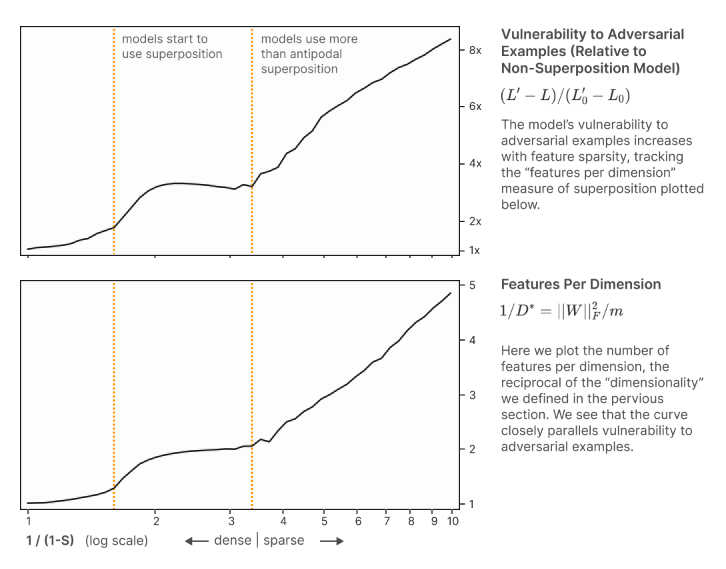

Toy Models Of Superposition has a section where they show a strong correlation between the susceptibility of their toy model to adversarial attacks and the 'amount' of superposition which their model is exploiting. Their model is a simple ReLU auto-encoder . They calculate this 'amount' of superposition as the 'number of features per dimension', which is the reciprocal of how they defined feature dimensionality:

where is the number of features. Below is the chart from the paper (link: https://arc.net/l/quote/laarnbmf)

I think the result, although interesting and notedly preliminary, is misleading, primarily due to the setup of their toy model. My reasoning is as follows:

Basically, because the toy model they use is an autoencoder, when perturbing any input feature that isn't in superposition in the hidden layer your loss won't change as the output will still match the input. On the other hand, when you change a feature that is represented in superposition, you can change the decoding of the model on other features, meaning a different input/output and a change to the L2.

Concretely, because the model has only one layer, the Jacobian of the encoder will be the identity if no features are in superposition. An identity Jacobian implies no cross-feature interference (any change to a single input component won't spill over into other features). Because they use MSE, a non-identity Jacobian (resulting from superposition) is what allows a perturbation to change the loss at all.

Their found correlation holds strongly because as you increase superposition you're just increasing the number of 'other' features you can change in the output, and this finding is not necessarily reflective of non-encoder models. The setup is a bit of a 'bug' for the adversarial task. Note also that while their attack is designed to be proportional to the attacked features dimensionality, this doesn't matter as the top chart is comparing to the non-superposition model, which should be completely robust if there is no noise in the weights (again because of the Jacobian argument).

Replicating their setup, this prediction holds on their model, and testing on a non-encoder model seems to show the relationship does not hold nearly as dramatically on normal models. I'll argue for this empirically below.

Empirical Evidence

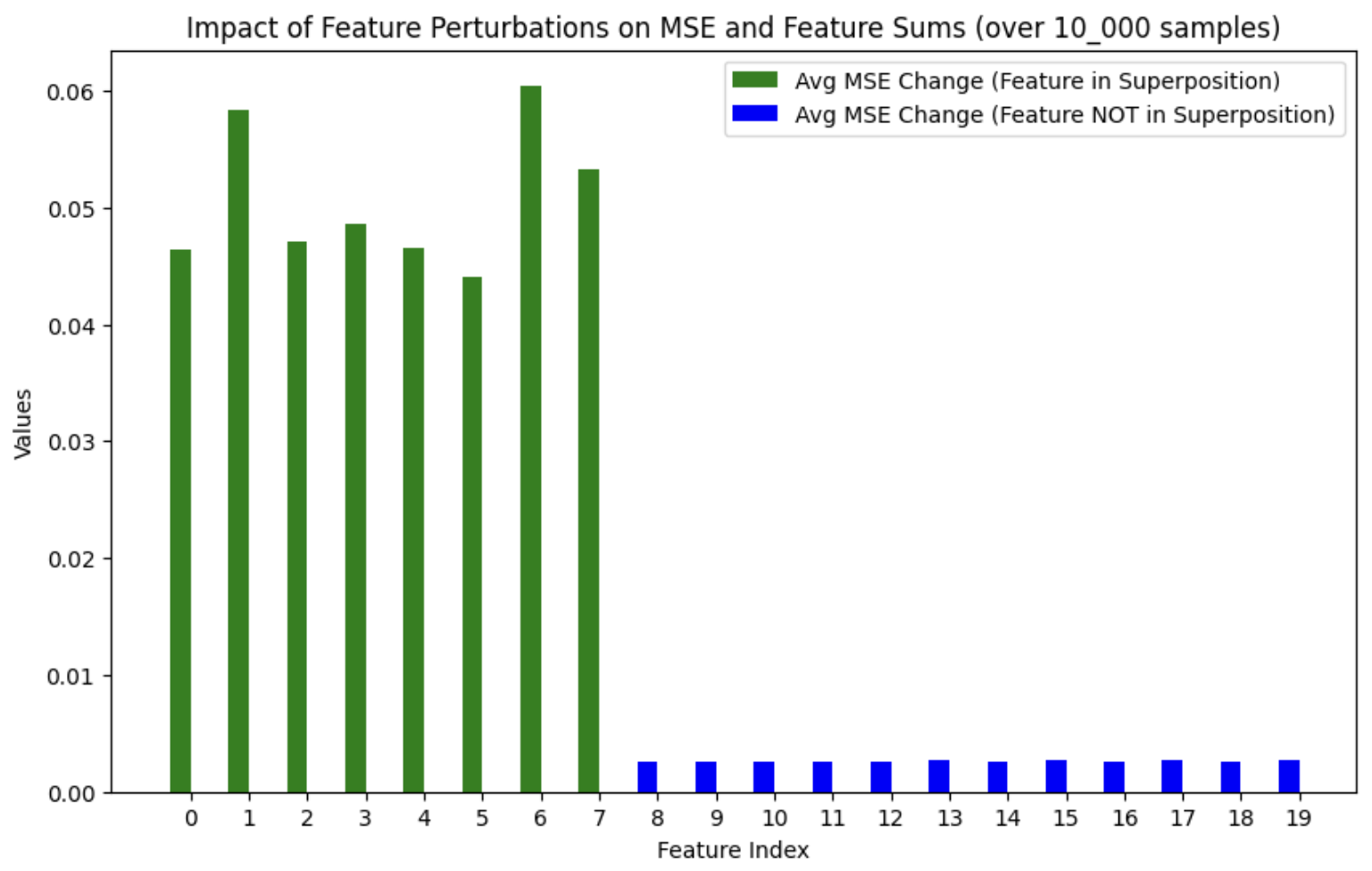

I replicated their toy model setup, training the ReLU model and using the same synthetic data setup. To induce predictable superposition, I used the same data as TMS, and manually set the first 7 features to be low importance and correlated, which does a good job encouraging the model to put them into superposition. Following the analytic method of attack detailed in the paper, , we can see that no feature not in superposition has the ability to significantly change the loss.

TMS Impact of Feature Perturbations on MSE

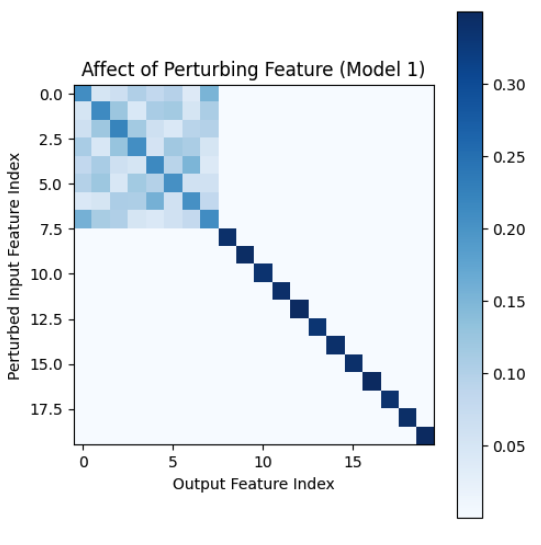

Perturbing features not in superposition is essentially unable to impact the loss. The small amount of change for features not in superposition is likely from the tiny amount of noise left in the weights. Here is a visual representation of the ability of an input feature to change an output feature for a model that has features 1-7 in superposition (essentially an empirical Jacobian):

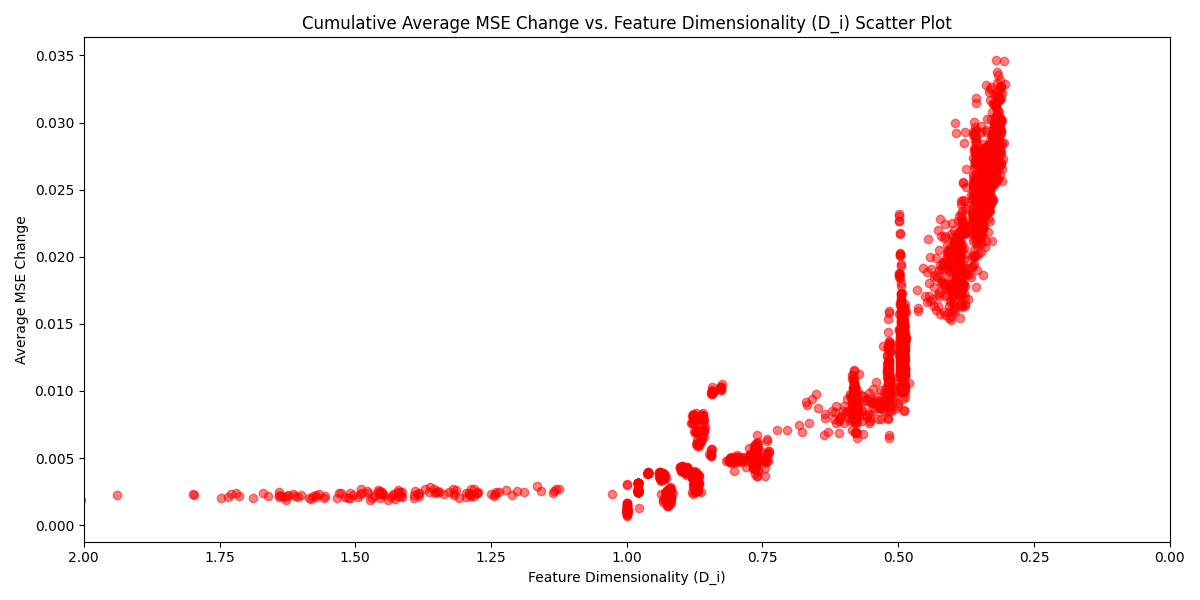

Plotting the average MSE with respect to feature dimensionality when analytically perturbing the input over a large number of samples, we see a strong trend where a decrease in feature 'dimensionality' results in a larger change to the MSE.

TMS Average MSE vs Feature Dimensionality

1 Layer ReLU MNIST Model

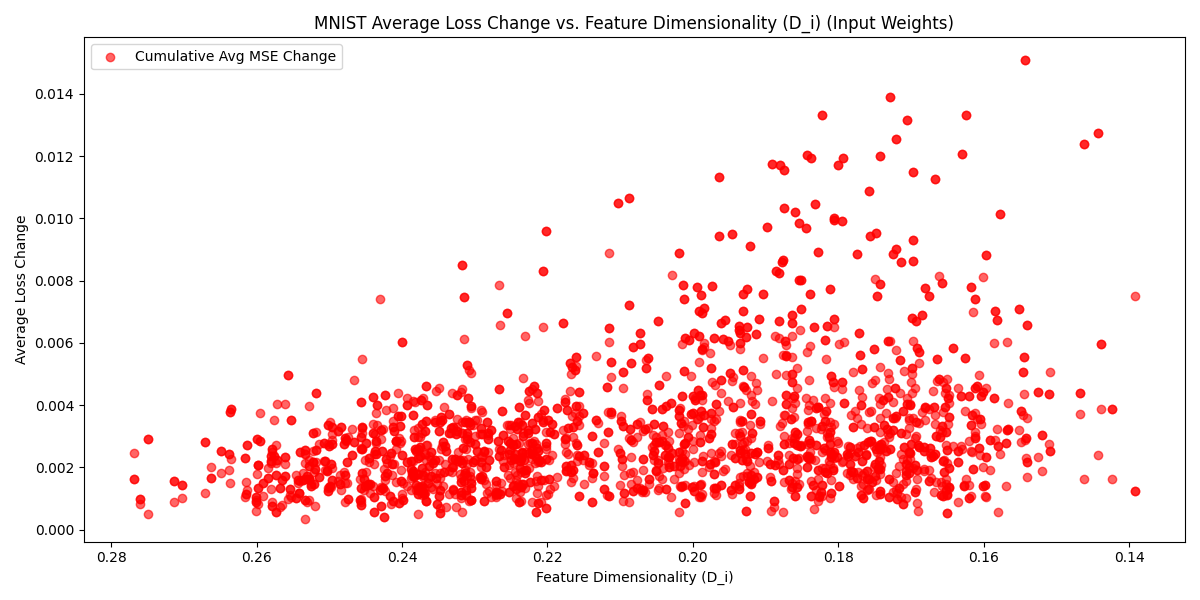

To sanity check whether this very nice looking trend carries over to other models, I trained a non-encoder model, specifically a one layer ReLU model with 28 neurons in the hidden layer, trained on MNIST (which has 784 input features). The significant difference between hidden and input dimensions suggests the model must use superposition to represent all features. Interestingly, we see some parallel between feature dim and loss, but not to the same extent as in the encoder model.

Effect of Analytically Perturbing Input Feature vs Feature Dimensionality (1 Layer ReLU MNIST Model)

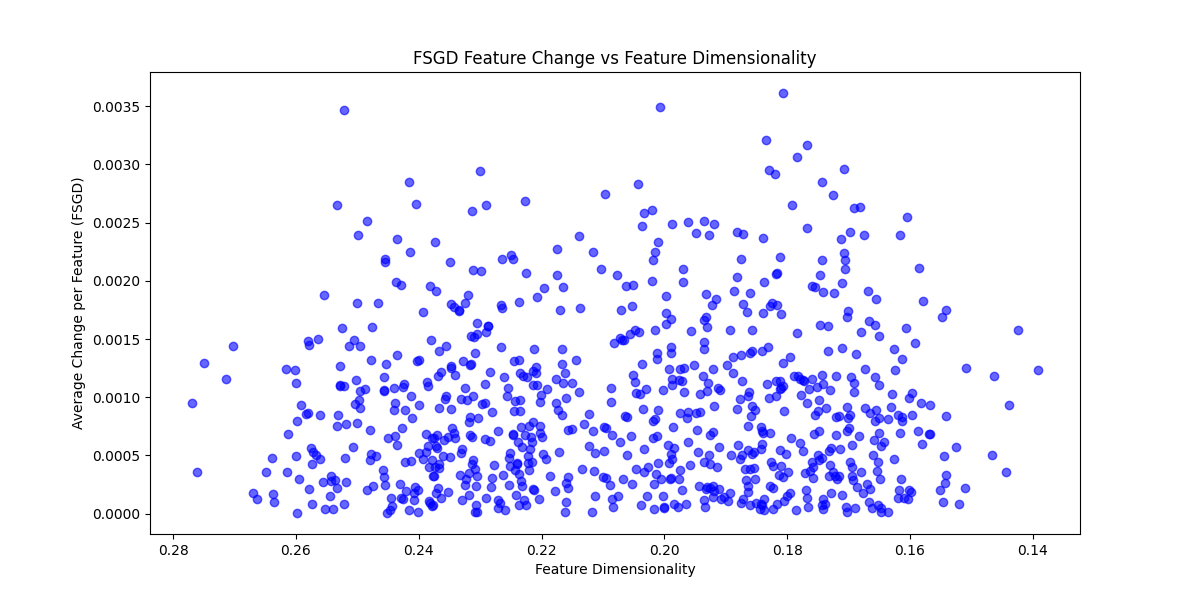

Now, to see whether non-analytic attacks (which perturb more than one feature) make use of this pattern we can plot feature dimensionality vs how often an analytic attack uses a feature in its attack. Naively using a common algorithm like Fast Sign Gradient Descent (FSGD) or Projected Gradient Descent (PGD) won't show this correlation because they perturb all features in the direction of the gradient, so when you average over a batch of data you end up with no correlation between and increase in MSE. For example, here's the average increase in MSE per feature over n samples vs feature dimensionality:

Average MSE Change Per Feature vs Feature Dimensionality

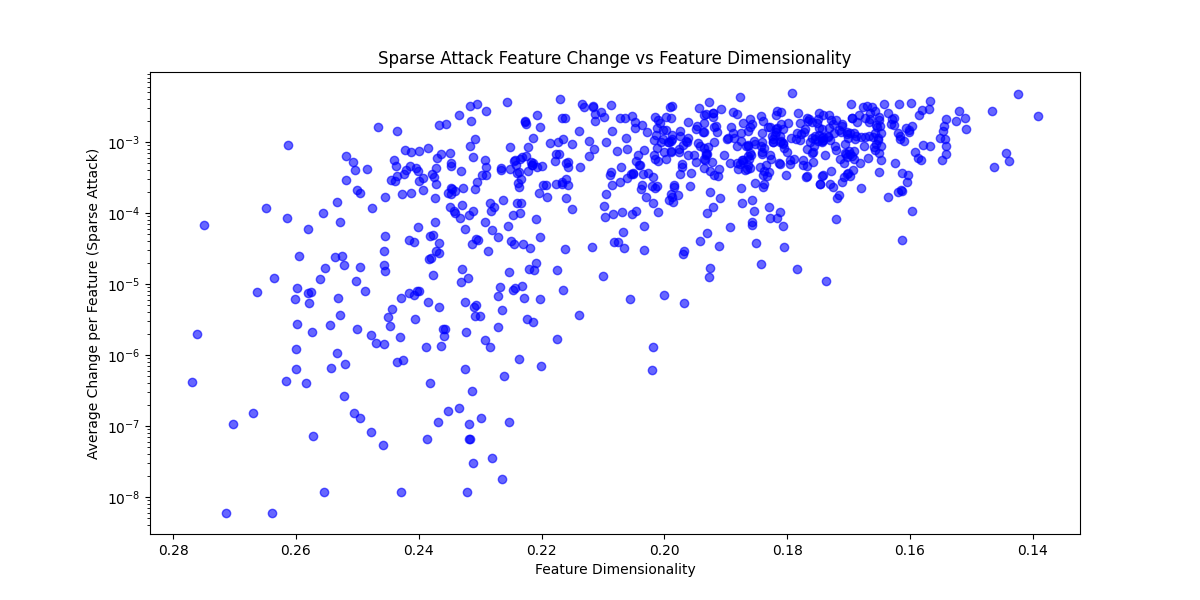

When constrained, an optimal attack would want to maximize output change per unit of perturbation. In this small model, it's reasonable to expect a constrained attack would choose to perturb features with the largest gradient norm. We can simulate this by modifying FSGD (or PGD) to only perturb along the top-k features w.r.t gradient norm. Here we see that features with lower fractional dimensionality get targeted much more often (Again on the MNIST model).

Top-K FSGD Attack Average Change Per Feature vs Feature Dimensionality

This correlation reinforces what we would expect - features in superposition are more involved in the loss, so their gradients are naturally bigger, which leads to them being targeted more often in a Top-K attack. Note also that features which are especially useful in predicting the output should also have large gradients

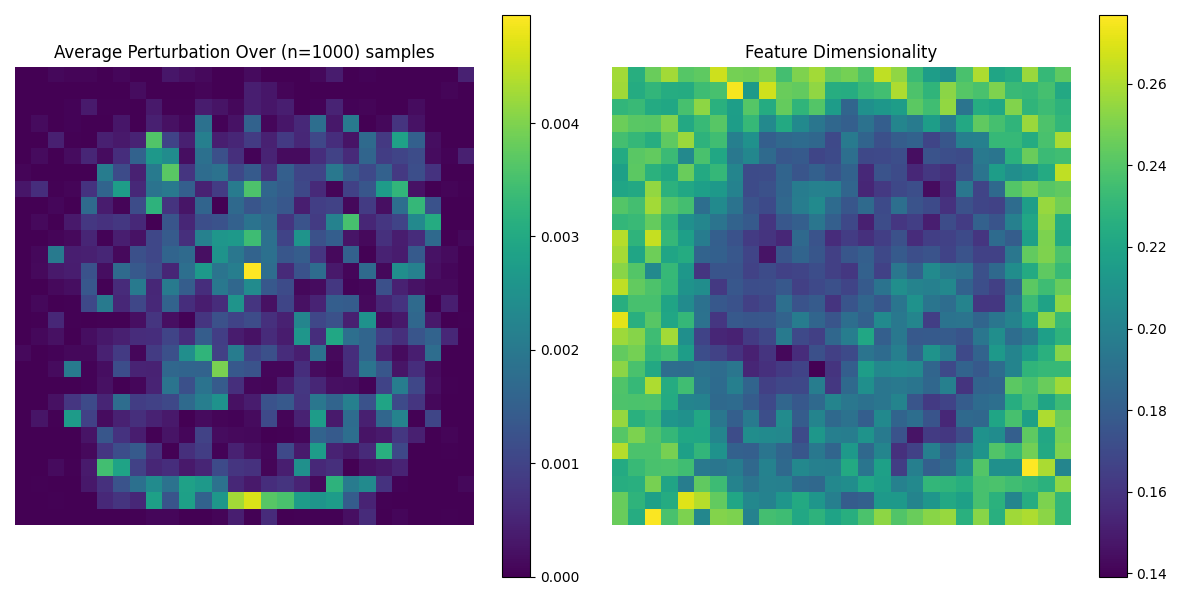

We can also directly inspect the average perturbations over the dataset vs the feature dimensionality.

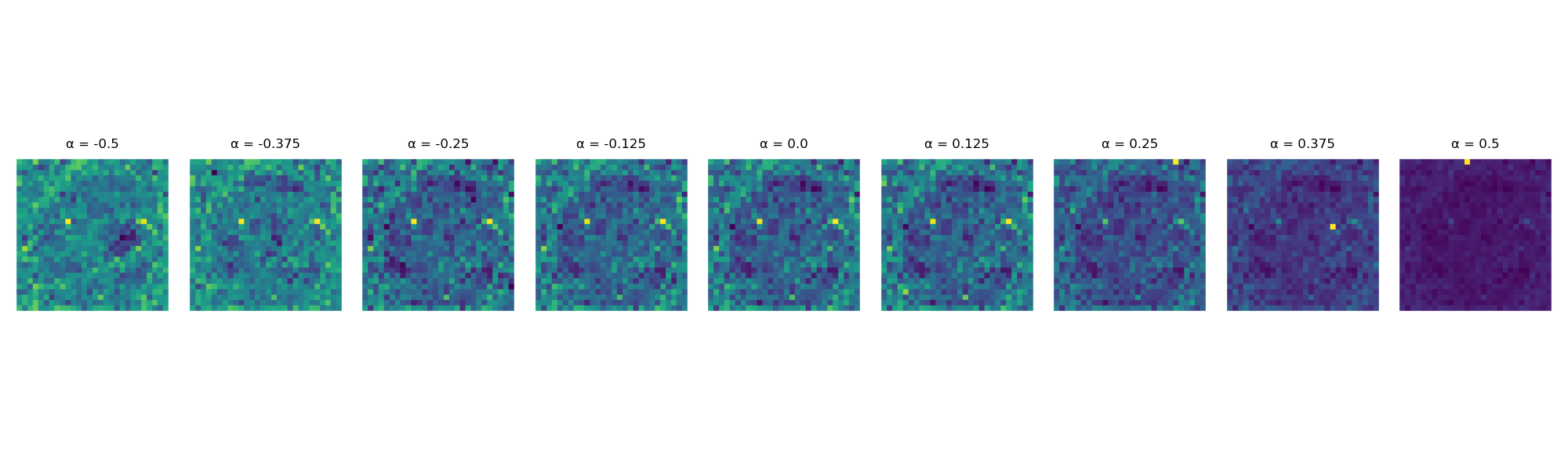

Average Perturbation and Feature Dimensionality of Input

The image on the left represents the average perturbations of 1000 different Top-K attacks. The image on the right shows the feature dimensionality for every feature in the input (a 28x28 Image)

Features in the center of the input image have a lower dimensionality. Visualizing the average perturbation per feature over a large batch, we can see, for the top-k FSGD, that these features in the center are the ones being attacked most, and also that the two graphs are ~inversely proportional.

The feature dimensionality findings are a little confusing to me; Intuitively, the features in the center are used more and are more important to prediction, but following the logic from TMS, important features should be more 'orthogonal' and therefore have higher dedicated feature dimensionality. My guess is features on the edges have a higher dimensionality because they fire very rarely, and when they do fire they are very useful in predicting a memorized 'pathological' example. Even though they're useful, an attack might not target these 'memorized' features because the amount of change needed to bring the feature into 'firing' is likely large. When we examine the above plots for MNIST models with varying hidden sizes, we can see that as superposition increases adversarial attacks make use of more of the input in their attacks, and as superposition decreases the model doesn't use the outer edges of the input at all.

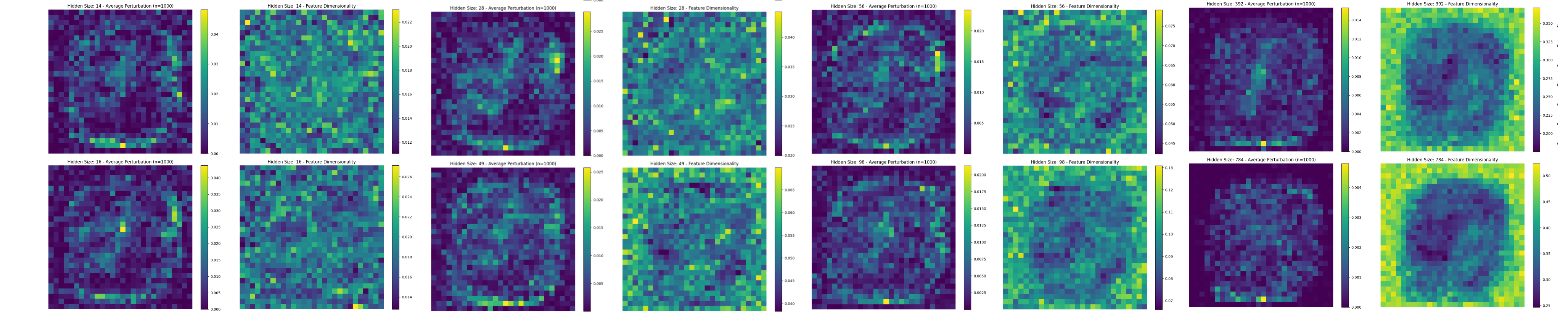

Average Adversarial Perturbations and feature dimensionality of models with different hidden sizes. As superposition decreases from left to right, total feature dimensionality increases around the edges and attacks start to exclusively target the center

Directly Intervening on Arbitrary Features

To more conclusively show that attacks are specifically targeting bits of the input in superposition, we can directly intervene on the dedicated dimensionality of a feature and look at the change in the average perturbation value.

Specifically, we can construct a linear transformation matrix that increases/decreases the feature dimensionality of a given feature by transforming the model's encoder weight matrix, , then freeze the transformed weights and fine-tune the decoder back to an equivalent loss. Fine-tuning the decoder effectively re-learns the mapping from perturbed latent space to output, ensuring that downstream performance isn't artificially degraded by the adjustment. Once fine-tuned, we can then re-run our adversarial attacks and calculate the difference in average attack on the feature . This determines if changing a feature's dimension changed its usefulness to an attack. We then sample this value over random features to obtain a result not dependent on feature importance.

The method in more detail is as follows:

Given a feature vector , we first normalize it:

We then construct an outer product matrix to represent the projection of any vector onto the direction of the normalized feature vector . We define a transformation matrix that adjusts the model’s weight matrix by either pulling it towards or pushing it away from the feature direction, controlled by a parameter :

- if , all the other feature vectors are pulled towards the feature vector , decreasing its feature dimensionality.

- if , all the other feature vectors are pushed away from the feature vector , increasing its feature dimensionality.

The adjusted weight matrix is then obtained by:

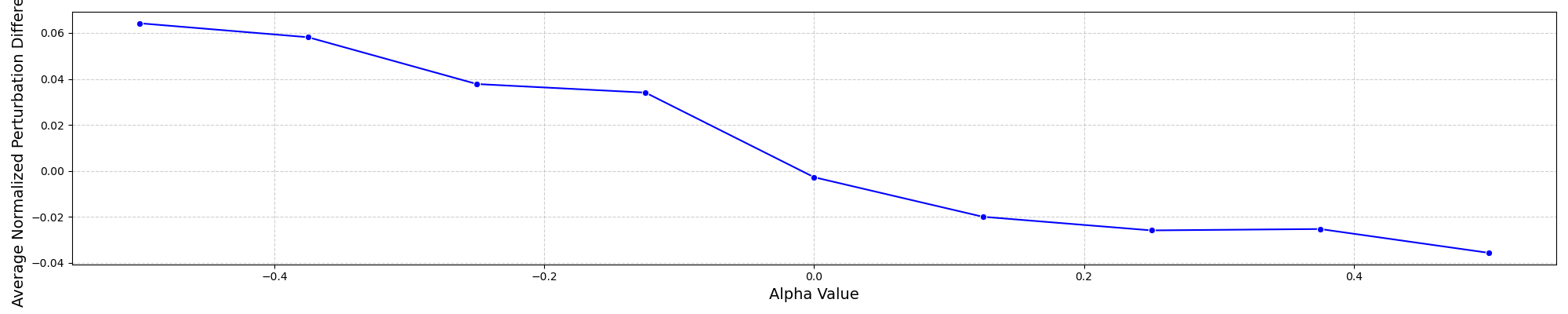

Varying from -0.5 to 0.5, we observe that adversarial attacks focus more on features with lower dimensionality and less on those with higher dimensionality, regardless of feature importance. The plot is sampled over 32 random features for each , and each feature was attacked 100 times with 100 steps of TopK-FSGD.

Average Feature Perturbation (TopK-FSGD) vs Feature Dimensionality

Images above plot are examples of feature dimensionality at the given of the adjusted weight matrix . When , the 'Average Normalized Perturbation Difference (ANPD)' goes up, indicating that adversarial attacks targeted this feature more often. When , ANPD is ~0, and when , the ANPD goes down, indicating that adversarial attacks targeted this feature less often.

Thoughts

Scaling to 'less toy' toy models is a target next step, but I don't think any metric of 'feature' dimensionality that attempts to tie input features to output changes over multiple layers will be meaningful (NOTE: my more recent post 'Interpreting Complexity' made a good start towards solving this using SLT) so tackling this problem in a real model might look more like using targeted attacks and then mechanistically examining representation changes. Features get recombined in complicated ways in larger models, so you'd miss out on nuanced changes to representations. If attacks do exploit superposition in larger models, it's likely that a targeted attack on something like an ImageNet model wouldn't just target arbitrary interference between features but instead interference in the direction of the target, which maybe could be tested empirically.

I also suspect that as you scale a model and its task, you're going to get more complicated, larger decision boundaries, and that at some point an attack will switch from exploiting just superposition to exploiting a hole in the decision boundary (as shown in 'The Space of Transferable Adversarial Examples'). Intuitively, even in real models, attacks should still preferentially target features with lower dimensionality over those with higher dimensionality, all else being equal.

What I really want to do next is train a toy model that keeps clusters of features in superposition, then run targeted adversarial attacks on these clusters. The paper 'The Persian Rug: Solving Toy Models of superposition using Large-Scale Symmetries' showed (in the toy-models-of-superposition setting) that as the number of features becomes large the interference from superposition is gaussian and basically becomes a summary statistic. I imagine that this would hold for large 'clusters' of features in superposition as well, so maybe adversarial attacks transfer because they a) exploit superposition, namely clusters that are relevant to the target, and b) the affect of an adversarial perturbation in two large enough clusters will be roughly the same because of the above.